And…it’s back.

Featured Plays: Antony and Cleopatra; Titus Andronicus; Macbeth; Richard II; Othello; As You Like It; Hamlet; Henry IV Part 1; Henry V

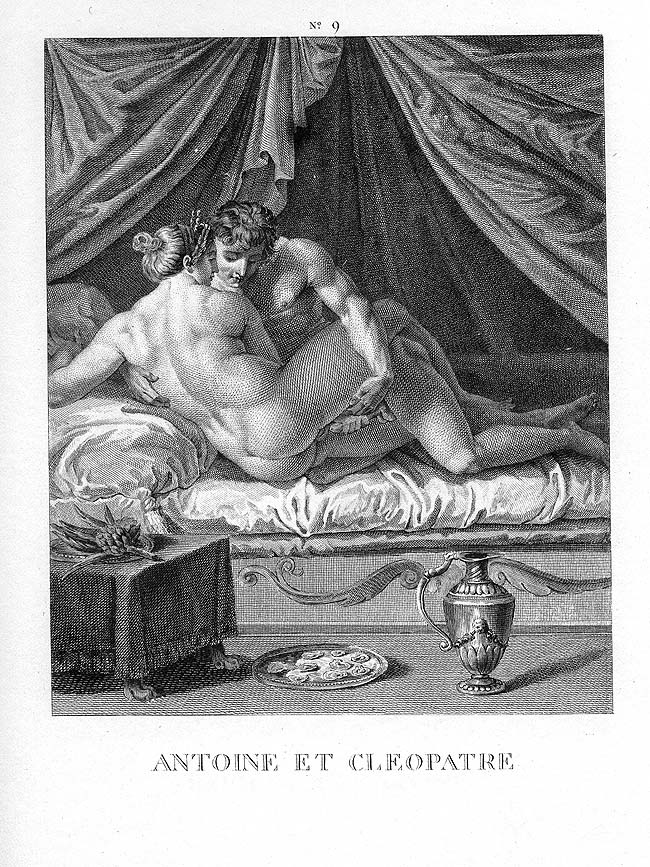

“KILLER QUEEN”—Antony and Cleopatra

By Agostino Carracci, Public Domain

What You Need to Know: If you HAVEN’T seen the Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton film (not based on the play technically…), then shame on you. In the olden days when it was still normal to cast white actors in non-white roles (oh wait), it was hard to imagine anyone who could embody the raw sexual power, vulnerability, and sheer force of will more than (or even close to) Elizabeth Taylor. She was a fusion bomb that could go off with a whisper but with the same capacity for destruction, always the flame who secretly wanted to be a moth. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra is all of this, and often maddeningly changeful. She’s a powerhouse, and in love with Antony, but he’s been away from Rome for too long and the remaining triumvirate, Octavius Caesar (Julius’ nephew and proclaimed heir) and Lepidus (Ancient Rome’s version of Westeros’ Littlefinger), either want to make war on him or with him. Antony’s wife in Rome and her brother led an army against Caesar, which they lost, so Antony has to go back and say he had nothing to do with it. He’s forced to marry Octavia, Octavius’ sister, to make peace—but he just winds up back in Alexandria. A lot of people get involved, and meanwhile, Cleopatra wants to keep Egypt’s autonomy, while Rome wants to make Egypt its most powerful colony. Then there’s more war, and eventually nearly everyone but Octavius dies.

*

If Moët et Chandon had been invented 1,783 years earlier than it was, it would most certainly have been drunk in Alexandria. And while the line “built-in remedy/For Kruschev and Kennedy” really points to the song’s subject as Christine Keeler, the archetype for this kind of woman, a weapon and a remedy, always starts with Cleopatra:

“Caviar and cigarettes/Well versed in etiquette/Extraordinarily nice/She’s a Killer Queen/Gunpowder, gelatin/Dynamite with a laser beam/Guaranteed to blow your mind/Anytime.”

Cleopatra is never without method, and even when she seems changeful, it is out of that suppressed vulnerability. She loves Antony, but she loves Egypt (and her power) just a little bit more:

Cleopatra: See where [Antony] is, who’s with him, what he does:/I did not send you:–if you find him sad,/say I am dancing; if in mirth, report/that I am sudden sick: quick, and return.”

Charmian: Madam, methinks, if you did love him dearly,/you do not hold the method to enforce/the like from him.

Cleopatra: What should I do I do not?

Charmian: In each thing give him way, cross him in nothing.

Cleopatra: Thou teachest like a fool,—the way to lose him.

She’s also bitter that he’s still married to Fulvia, even though she learns Fulvia is dead about a minute later. And while there is no woman who can compete with Cleopatra, her real worry is that Antony will always be ‘married to’ Rome. But she is never a cold, passive leader, even when she does play at being changeful.

According to Queen, at the “Drop of a hat she’s as willing as/Playful as a pussy cat/Then momentarily out of action/Temporarily out of gas/To absolutely drive you wild, wild…/She’s all out to get you.”

Whenever Cleopatra is with Antony, the level of sexual arousal gets turned up to eleven. When Antony tells her he has to go back to Rome in Act I, scene iii, she gives the very loaded line, “I would I had thy inches; thou shouldst know/there were a heart in Egypt,” and Antony’s reply is, “my full heart/remains in use with you,” and then there’s some back and forth in which she never permits Antony to give the right answer, and the level of the bantering is a tease into a verbal copulation which ends, “Sir, you and I must part, —but that’s not it:/sir, you and I have loved.—but there’s not it: that you know well: something it is I would,—O , my oblivion is a very Antony, and I am all forgotten.” The rhythm and the dropped lines, yes, could be grief, but the panting denotes not just crying, but a crying out in ecstasy, punctuated by the great ‘O.’ One exchange later, Antony concludes: “Let us go. Come…” Shakespeare’s wonderfully layered wordplay here gives us everything that can’t be shown on stage. It is complex and delightful and befitting a richly complex figure.

“FLICK OF THE WRIST”—Titus Andronicus

Illustration from Titus Andronicus from Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of Shakespeare’s Complete Works [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

What You Need to Know: This is Shakespeare’s bloodbath tragedy, which is saying something. It’s one of his earliest plays, and 18th century critics panned it for its violence and amateurism. However, there’s a lot to be learned here about Shakespeare and his ideas of revenge. And this is a distinctly Roman play—18th century England was just in its uptight, post-Puritan era so didn’t fully appreciate the importance of the gore. Titus Andronicus is the general of the Roman army, returned after defeating the Goths and bringing the prisoners, especially Queen Tamora, her three sons, and her lover, Aaron, back for the conquest. Titus demands a sacrifice to the gods for the death of his sons in battle, deciding on Tamora’s oldest son Alarbus. She begs Titus to spare his life, but Titus is rigid and says the gods demand it. This sets off a cycle of revenge in the best example of one-upmanship in the history of drama. The next day, the senate offers Titus the job of, you know, Emperor of Rome, which he turns down. The previous emperor’s two sons are vying for which one should be emperor…Saturninus, the eldest, or Bassianus, the most qualified and likeable and betrothed to Lavinia, Titus’s daughter. Titus says it should always go to the eldest. Saturninus, grateful, says as a gesture of thanks, he will marry Lavinia. Titus says “okay,” but Lavinia, Bassianus, and all Lavinia’s brothers prevent this and help her flee. In the process, Titus kills his youngest son for betraying him, and then he promises Saturninus that he’ll fix it…but then the new emperor goes and marries the former prisoner, Tamora. Suddenly, a mother with a grudge gets a whole lot of power. She has her two remaining sons, Chiron and Demetrius, murder Bassianus, rape Lavinia and cut out her tongue and chop off her hands, leaving her for dead, and blame the murder on two of Titus’s remaining sons. Shakespeare’s other Killer Queen, in a very literal sense. Tamora’s still-lover Aaron tells Titus he can have his sons back if he’s willing to chop of his hand in exchange. He does, and gets back his sons’ heads. Then he finds Lavinia. After he eats his own humble pie, he then looks up some really good recipes for Tamora…

*

When Queen sings, “Flick of the wrist – he’ll eat your heart out/A dig in the ribs and then a kick in the head/He’s taken an arm and taken a leg/All this time honey/Baby you’ve been had,” they could be singing to poor Lavinia. Sure, the literal “he” in this case would be “they,” for Chiron and Demetrius, but in a way, her father Titus led to all this violence by showing no mercy to Tamora as she pled for her own son’s life. Titus was so rigidly locked in to honoring the gods, he was blind to all else, including obvious consequences. The price was the loss of all his children but one. There turns out to be a lot of wrist-flicking, especially when the arms end at that point.

What Shakespeare sets up in this play and continues thematically throughout the rest of his plays is that revenge never pays off; at best, it is a Pyrrhic victory (referenced specifically, by the way, in Hamlet, when young Hamlet talks to the players about the best performance of theirs he remembers, and then finishes the actor’s recitation of the lines of Pyrrhus). At the end of Titus Andronicus, both Titus and Tamora get surviving heirs, a hopeful but still ambiguous ending that maybe there is still a chance for the cycle of violence to end. Or continue.

Illustration of a review in The Moving Picture World June 1916 [Internet Archive/Public Domain]

Illustration of a review in The Moving Picture World June 1916 [Internet Archive/Public Domain]

What You Need to Know: Welcome back to 10th Grade. Macbeth is the Lancelot to Duncan’s King Arthur; he’s the super-warrior who defeats (almost single-handedly) the army of a rebellious thane (duke) of medieval Scotland. Then he and his buddy Banquo run across three “weird sisters” (who do turn out to be witches—if you’ve only seen the films, you miss the fact that Hecate shows up in the play to talk to them), who give Macbeth a prophecy that he’ll be Thane of Cawdor and then King of Scotland (on top of his current title, Thane of Gamis). In a series of contradictions, Banquo’s prophecy is that he’ll be less happy than Macbeth and more happy because his son will set up a perpetual line of succession of kings. At first, Macbeth and Banquo find this amusing and joke about it…until Duncan’s messenger arrives to give Macbeth the title of Thane of Cawdor. So Macbeth IMMEDIATELY thinks: hmm, should I murder Duncan so I can be king? And then writes to his wife about it. Lady Macbeth is all in. Then Macbeth has doubts, then Duncan says he’s naming his son Malcolm as his heir and tells Macbeth to help out Malcolm and watch over him. Now that’s two people Macbeth has to jump over to become king. And the shortest way between two kings is a straight blade. He kills one, and Malcolm escapes to England. Meanwhile, Macbeth decides it’s not enough to be thus but “to be safely thus,” and so murders Banquo, who knows about the prophecy, tries to murder Banquo’s son, tries to murder Macduff—a thane loyal to Duncan and possibly suspicious of Macbeth (actually, let’s be real, everyone is suspicious of Macbeth; he never fools anybody)—but gets Macduff’s wife, kids, and household instead. Meanwhile, what happens when you’re king? You have no equal—and so Lady Macbeth is left out. As their separation grows, their security shrivels.

*

There’s an old saying that patience is a virtue. Macbeth hasn’t heard that one. Queen sets up the scene: “Just an alley creeper, light on his feet/A young fighter screaming, with no time for doubt/With the pain and anger can’t see a way out/It ain’t much I’m asking, I heard him say/Gotta find me a future move out of my way/I want it all, I want it all, I want it all, and I want it now.”

Upon first hearing the prophecy from the witches, Macbeth says, “to be king stands not within the prospects of belief, no more than to be Cawdor,” but as soon as he’s named Cawdor, he tells himself, “Two truths are told,/ as happy prologues to the swelling act/of the imperial theme,” and then immediately after, “This supernatural soliciting cannot be ill, cannot be good;—if ill,/why hath it given me earnest of success,/commencing in a truth? I am thane of Cawdor:/if good, why do I yield to that suggestion/whose horrid image doth unfix my hair,/and make my seated heart knock at my ribs,/against the use of nature?” So even though he later thinks, “If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown my,/without my stir…” but that first thought there was to jump to murdering Duncan. Maybe Duncan would have pulled a Pope Benedict and retired? Maybe Malcolm would have tripped over a rake and land in a bog? Been eaten by a seal? Who knows? The point is that Macbeth doesn’t bother waiting to find out. Because he’s an idiot.

Queen: “I gotta get me a game plan, gotta shake you to the ground/But just give me what I know is mine.” Unfortunately for Macbeth, he doesn’t have much of a game plan. Lady Macbeth says she’ll handle it all, and when it’s the set time to commit the murder, he imagines a dagger in his hand (“is this a dagger I see before me?”), and no sooner than he imagines it but the deed is done. And he forgets to plant it on Duncan’s guards, so Lady M has to go back and fix it.

Or, as Macbeth says in III. iv.: “I am in blood stept in so far, that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o’er.” Might as well keep going, see it through. It’s not like he’s slept since Duncan’s murder.

The biggest tragedy of Macbeth is that he and Lady Macbeth were a happy couple who stood to lose everything. That’s why the Justin Kurzel Macbeth of 2015 is so frustrating. The film opens with the burial of the Macbeths’ baby. This seems to inform the characters of Macbeth and especially Lady Macbeth throughout the film. During her famous “Out, damn spot,” speech, Marion Cotillard delivers her lines to the ghost of her son. Uh…what? Let’s look at history for some necessary context. We can pretty much agree that Shakespeare employs regular anachronism, and that even though set in Medieval Scotland (or for other plays in Ancient Rome or Greece), life described fits Elizabethan London more than any other place. It’s like Italo Calvino’s Marco Polo in Invisible Cities—all cities are Venice. During Shakespeare’s time, infant mortality was about 1/3. Think about what a jarring figure that is. During the plague the year before Shakespeare’s birth, a quarter of London’s population was wiped out. And then Shakespeare lived through another awful plague in 1593, in which about 11,000 people were killed. The average life span was 30-40 years. So mortality was something confronted every day (not to mention all the public executions and bodies left to hang and rot, even along the Tower Bridge). Death was something that Elizabethans coped with to a greater degree than most of us can imagine. So when the play’s Lady Macbeth gives that awkward, totally weird speech in I. vii.: “What beast was’t, then,/that made you break this enterprise to me?/when you durst do it, then you were a man;/and, to be more than what you were, you would/be so much more the man…I have given suck, and know/how tender ‘tis to love the babe that milks me:/I would, while it was smiling in my face,/have pluckt my nipple from his boneless gums,/and dasht the brains out, had I so sworn as you/have done to this,” you might expect Macbeth to be horrified at this, but his comment is, “If we should fail?” So…he’s clearly not so concerned about the image of his baby’s brains dashed out. But this is an important moment and often misrepresented (and misunderstood). They both have survived the death of their infant. It was probably horrible but not a shock. Even Shakespeare had older siblings that did not survive infancy, and his own son Hamnet died as a boy. And then he went on to write Hamlet. So yes, he felt it…but it did not destroy him, as it did not destroy the Macbeths. And this is all well before we meet them in the play. So the Macbeths feel as though they’ve gone through the worst of it and have come out okay. They survived the death of a child—sure they love Duncan, but they can survive his death, too. They have each other, and that’s a lot for love (wait, wrong band). The problem is that infant mortality is WAAAAAAAAY different from murdering the king. And THAT’S what they don’t take into account. The guilt. Which destroys them. Shakespeare’s Macbeths still have everything to lose. They have good lives, Macbeth is a beloved war stud, Lady Macbeth is beautiful and beloved by everyone, especially her husband, and is an equal partner. Michael Fassbender and Cotillard…they just feel like they’re marking time (a sad waste of two exquisite actors, who make you want to believe in their performances but are impossible to like because they’re just too evil).

EX17097 The entry of Richard II and Bolingbroke into London by Northcote, James (1746-1831) Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, Devon, UK English, out of copyright

What You Need To Know: This is the play that begins Shakespeare’s “Lancaster Tetralogy,” how Henry Bolingbroke takes the throne from his cousin, Richard, the last Plantagenet king, and becomes Henry IV (whoops, spoiler), the first of the Lancaster kings, then onto the legacy of his son and grandson, Henry V and Henry VI. The histories are often complicated with a full cast of similarly-named characters with grudges or allegiances going back generations. This play begins with an exchange between Bolingbroke (Duke of Hereford) and Thomas Mowbray (Duke of Norfolk), each throwing down the gauntlet (although here, they’re throwing their gages, which just sounds more like a hissy fit) over Mowbray’s attempted murder of Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt, and the king, a while ago, and also the actual murder of the Duke of Gloucester, Gaunt’s brother. Mowbray accuses Bolingbroke of random stuff. They agree to dual, and things get awkward because, as it turns out, King Richard II may have had a hand in Gloucester’s murder. Gloucester’s widow wants Gaunt to avenge him, which he won’t do because Gaunt is old school and believes that kings are appointed by God. When the dual between Mowbray and Bolingbroke does take place, Richard listens to their accusations again, and just when things are about to get started, he stops them and tells Bolingbroke he’s going to be banished for ten years (but then cuts it down to six), but that Mowbray (Norfolk) will be banished for life. John of Gaunt is not pleased at the loss of his son. Then, Richard isn’t pleased when he hears how much the public adore Bolingbroke and says maybe he won’t let Bolingbroke ever come back to England. Things get worse when Richard, who spends too much money on his court and already borrows money from his lords and over-taxes the poor, wants more money to have a war in Ireland. Gaunt disapproves, but he dies, and Richard seizes Gaunt’s lands, even though by rights Bolingbroke is still entitled to inherit them. Here’s where some of the other lords, notably Northumberland, back out and side with Bolingbroke. Before long, everyone is siding with Bolingbroke, who has rallied an army in Brittany and storms England in an almost-bloodless revolution while Richard is away in Ireland. Most of England now has sided with Bolingbroke, and when Richard returns and finds that even his Welsh army has defected, he hides until Bolingbroke comes to demand his lands back/arrest him. Bonlingbroke then wants to round up any final conspirators, including solving the mystery of his uncle Gloucester’s death.

*

What Queen says: “Then came a man before His feet he fell/Unclean said the leper and rang his bell/Felt the palm of a hand touch his head/Go now go now you’re a new man instead/All going down to see the Lord Jesus…”

This one’s a stretch, but…Jesus and death can resolve old conflicts, at least in Richard II:

Aumerle: Some honest Christian trust me with a gage./That Norfolk lies, here do I throw down this,/ If he may be repeal’d to try his honour.

Bolingbroke: These differences shall all rest under gage/ Till Norfolk be repeal’d: repeal’d he shall be,/ And though mine enemy, restor’d again/ To all his lands and signories; when he’s return’d,/ Against Aumerle we will enforce his trial.

Bishop of Carlisle: That honourable day shall ne’er be seen./ Many a time hath banish’d Norfolk fought/ For Jesu Christ in glorious Christian field,/ Streaming the ensign of the Christian cross/ Against black pagans, Turks, and Saracens;/ And toil’d with works of war, retir’d himself/ To Italy; and there at Venice gave/ His body to that pleasant country’s earth,/ And his pure soul unto his captain Christ,/ Under whose colours he had fought so long.

Bolingbroke: Why, bishop, is Norfolk dead?

Bishop of Carlisle: As surely as I live, my lord.

Bolingbroke: Sweet peace conduct his sweet soul to the bosom/ Of good old Abraham! Lords appellants,/ Your differences shall all rest under gage/ Till we assign you to your days of trial.”

Bolingbroke was going to bring Norfolk (Mowbray) back from exile to testify against other potential conspirators in the murder of his uncle, but he learns that Norfolk died in a Crusade, fighting for Jesus. He wanted to bury the hatchet (in Aumerle’s skull), and now can make peace with his old nemesis retroactively. He actually forgives Aumerle (twice, in fact, since Aumerle is later part of a plot to murder Bolingbroke after he becomes King Henry IV). This is the forgiving play. Except for Richard II. The new King Henry sort of almost hints that he should be killed, and somebody’s sword slips, etc.

And they all lived happily ever after and never was there war again. The end.

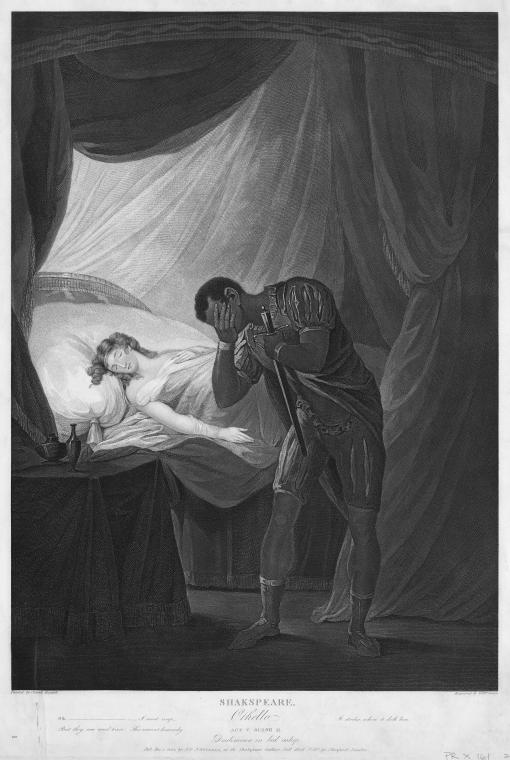

Desdemona Asleep in Bed By Josiah Boydell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

What You Need to Know: Venice is fighting the Turks over Cyprus. Iago has been passed over for Lieutenant in favor of Cassio, a Florentine. The general who has done this is Othello. Is Iago just jealous that he’s been passed over? In a word, no. We never truly know what Iago is thinking deep down, or his initial motivations. Iago, as he tries to think of another reason for hating Othello, says he might have heard somewhere someone say Othello once slept with Iago’s wife Emelia; Iago doesn’t know for certain, but he’ll take it as truth so he can be justified in hating Othello. Does Iago really think Othello’s done this? Probably not, and by the way Iago treats Emelia, he probably wouldn’t have cared as long as he’d been made Lieutenant. But Iago is kind of attracted to Othello, kind of attracted to Othello’s wife Desdemona, and is also kind of attracted to Cassio. It’s the ultimate inferiority complex. It’s a little like the serial killer mentality—he wants to be subversive and commit wildly-plotted crimes, but he also wants people to take note of how clever he is. He starts by ruining Cassio’s reputation and gets him fired, and then he makes Othello believe that Cassio is sleeping with his beloved Desdemona. And believe him he does. To awful, awful consequences. This play, for me, is the most tragic, most depleting, of all Shakespeare’s oeuvre. Lear and Hamlet follow, and I refuse to teach a combination of any of these three in a single semester. I’d be a sadist and a masochist.

*

Queen’s song begins: “Oh how wrong can you be?/Oh to fall in love was my very first mistake/How was I to know I was far too much in love to see?/Oh jealousy look at me now/Jealousy you got me somehow/You gave me no warning/Took me by surprise/Jealousy you led me on.”

This one is a bit of a no-brainer for Othello. Some may argue that it could be about Claudio, from Much Ado. However, let’s take a look at the ending to “Jealousy”:

“I wasn’t man enough to let you hurt my pride/Now I’m only left with my own jealousy/But now it matters not if I should live or die/’Cause I’m only left with my own jealousy.”

Claudio has no problem moving on after he spurns Hero, even after he hears Hero has died. He finally gets upset when he gets the proof from Dogberry and Verges that Hero was innocent and that he made a mistake. Maybe the song could be about The Winter’s Tale’s Leontes, but even he isn’t quite so tortured by jealousy…for which he has no one to blame but his own stupidity. (The guy is really an ass.)

So therefore, no one is more torn up by jealousy while still being in love than Othello. It takes a vindictive genius to work on him and work on him. Iago also happens to be preying on Othello’s status as an outsider to Venetian culture. Yes, he’s a moor, but Venetians are quick to judge Cassio as well, who is a Florentine. Venice reveres Othello for being a great general and appears to be a good leader of men, well respected as governor of Cyprus for the few days he is, and generally liked by all. But Iago works on him, letting him know that Othello’s place in this culture is shaky, nebulous. He sneaks in racist terms (mostly, he plays the Trump card and says racist things about Othello to other people, getting them to show their true racist colors. See what I did there with that pun?). And Iago is able to turn Othello into an actual shadow, to a point that Othello’s body begins to betray him. Even the setting for this play has to be outside Venice, but not quite the Middle East—Cyprus is as much an in-between entity as Othello.

And he and Desdemona really love each other, and they really love being married and doing the things rich, powerful married people get to do (take a night off work, leave a lieutenant in charge, and get busy). It’s a short, but happy honeymoon. Too bad they invited Iago, the worst villain in all literature, and John Milton’s model for Lucifer in Paradise Lost.

Othello’s tortured speech before he goes to murder Desdemona is enough to make even Goebbels misty-eyed: “It is the cause, it is the cause, my soul,—/let me not name it to you, you chaste stars!/it is the cause.—Yet I’ll not shed her blood;/nor scar that whiter skin of hers than snow,/and smooth as monumental alabaster./Yet she must die, else she’ll betray more men.—/Put out the light, and then put out the light:/If I quench thee, thou flaming minister,/I can again thy former light restore,/should I repent me: —but once put out thy light,/though cunning’st pattern of excelling nature,/I know not where is that Promethian heat/that can thy light relume. When I have pluckt the rose/I cannot give it vital growth again,/it needs must wither: —I’ll smell it on the tree…” and then he kisses her in her sleep, then continues: “O balmy breath, that dost almost persuade/justice to break her sword!—One more, one more: —/but thus when thou art dead, and I will kill thee,/and love thee after:—one more, and this the last:/so sweet was ne’er so fatal. I must weep,/but they are cruel tears: this sorrow’s heavenly;/it strikes where it doth love.”

If you know what Iago has said to Othello to prime him, this speech is even worse. Othello is no fool. Iago’s is the ultimate betrayal…and the hardest to get at, because he manages to allude even us, even after over 400 years.

“DOING ALL RIGHT”—As You Like It

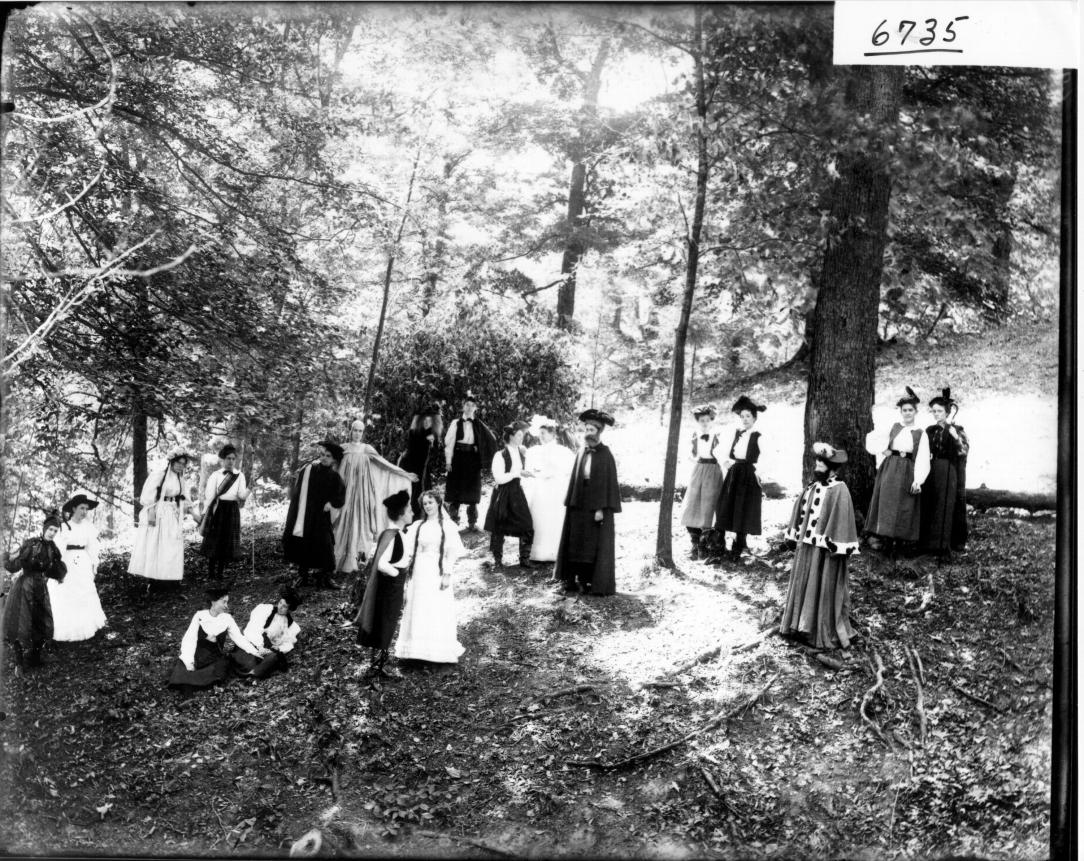

Scene from 1905 Production of As You Like It By Snyder, Frank R. Flickr: Miami U. Libraries – Digital Collections [No restrictions or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Scene from 1905 Production of As You Like It By Snyder, Frank R. Flickr: Miami U. Libraries – Digital Collections [No restrictions or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

What You Should Know: The characters of this play are ultra-rebounders. Rosalind’s sad about her father’s exile? Celia says when her own usurping father dies, she’ll make Rosalind the true heir. Rosalind celebrates by deciding to fall in love. The solution to exile? A sylvan bacchanal. The girl who’s been an asshole to you the entire play suddenly agrees to marry you? Accept! And the god Hymen will bless the marriage. Kenneth Branagh screws up the adaptation and culturally appropriates 18th Century Japan for absolutely no good reason? The Globe Theater kills it with an amazing performance and my favorite Jacques.

*

The lyrics “Yesterday my life was in ruins/Now today I know what I’m doing/Got a feeling I should be doing all right” could be straight out of the mouth of the Duke Senior:

“Now, my co-mates and brothers in exile,/hath not old custom made this life more sweet/that that of painted pomp? Are not these woods/more free from peril than the envious court?/Here feel we but the penalty of Adam,/The season’s difference; as the icy fang/and churlish chiding of the winter’s wind,/which, when it bites and blows upon my body,/even till I shrink with cold, I smile, and say/ ‘This is no flattery; these are counsellors/that feelingly persuade me what I am.’/Sweet are the uses of adversity…and this our life, exempt from public haunt,/finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,/sermons in stones, and good in every thing:/I would not change it.”

He’s making the most of his exile and is in no hurry to leave. He has all his best friends, and doesn’t even seem to miss his daughter that much. Maybe because, now that he’s not in charge, he can be his randy self in a forest full of men.

“NEED YOUR LOVING TONIGHT”—Hamlet

Hamlet and Ophelia-Compositional Study by Dante Gabriel Rossetti [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Hamlet and Ophelia-Compositional Study by Dante Gabriel Rossetti [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

What You Need to Know: Yes, Hamlet and Ophelia have had relations. “Indeed” is the same as “in deed” when Ophelia tells Hamlet how he made her believe he loved her. And then he toys with her poor little emotions because he’s sure he’s being watched by her father and his uncle, The King. All while Hamlet’s trying to decide whether to murder his uncle like the ghost of his father (who is in hell) told him to do. Ophelia is torn between her love for Hamlet and duty to her (abusive) father, Polonius.

*

Queen uses a very important image in this song: “No I’ll never look back in anger,/No I’ll never find me an answer,/You promised me you’d keep in touch/I read your letter and it hurt me so much/I said I’d never, never be angry with you./I don’t wanna feel like a stranger/Cos I’d rather be in danger/I read your letter so many times/I got your meaning between the lines/I said I’d never, never be angry with you.”

And the song complicates the character of the singer more with: “Come on baby, let’s get together/I’ll love you baby, I’ll love you forever/I’m trying hard, to stay away/What made you change, what did I say?/Ooh I need your loving tonight/Hit me.” This is someone who is willing to undergo a lot of misery to be with her love.

Oh, Hamlet has a letter. Boy does Hamlet have a letter. It gets sent to Ophelia, who is the singer of Queen’s song. The letter, which is intercepted by Ophelia’s father Polonius and then read to King Claudius, includes a love poem: “Doubt thou the stars are fire;/Doubt that the sun doth move;/Doubt truth to be a liar;/but never doubt I love./O dear Ophelia, I am ill at these numbers; I have not art to reckon my groans: but that I love thee best, O most best, believe it. Adieu. Thine evermore, most dear lady, whilst this machine is to him…”

There have been problems decoding this poem and message for centuries; one critic even describes the letter as a type of Rorschach for Hamlet to turn the mirror back on the other characters and assess them—as well as the playgoers. Ambiguity plays an essential role through this play, as we are constantly doubting everything that is presented to us. What we don’t doubt is that Ophelia loves Hamlet, and despite waiting with Job-like patience for his return from school, once he encounters the ghost of his father, he pulls away from her almost completely. Hamlet is much more like his uncle Claudio than his warmonger father, whom he apotheosized.

When Hamlet, Horatio, and Marcellus are waiting for the appearance of the ghost in I.iii, they can hear from outside the revels from inside the court, and Hamlet, waiting nervously for his father’s apparition, rolls his eyes, “It is a custom/more honour’d in the breach than the observance./This heavy-headed revel east and west/makes us traduced and taxt of other nations:/they clepe us drunkards, and with swinish phrase/soil our addition; and, indeed, it takes/from our achievements, though perform’d at height,/the pith and marrow of our attribute.”

This sounds severe for someone who is a 30-year-old college student, loves the theater, wants to be an actor, and makes overt sexual references to his girlfriend in front of the court:

Hamlet: Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

Ophelia: No, my lord.

Hamlet: I mean, my head upon your lap?

Ophelia: Ay, my lord.

Hamlet: Do you think I meant country matters?

Ophelia: I think nothing, my lord.

Hamlet: That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.

Ophelia: What is, my lord?

Hamlet: Nothing.

Ophelia: You are merry, my lord.

Aside from the punning on lie (everything is in question in this play), replace lap with lip, say “country” out loud and then take out the “ry,” understand “nothing” is a pun on “noting” and “no-thing” (vagina), realize that “thought” here is a pun on the idea within this speech but also within the context of the play, and that “merry” means horny or aroused. This is the guy who is annoyed by Act I’s bacchanal (admittedly, involving his mother and uncle—it might turn anyone off sex for a while). It’s also the same personality shift that happens when your friends are watching Caligula at your house and your dad comes in and you have to act like it wasn’t your idea and say you confused it with I Claudius.

Another consideration: Hamlet is an obsessive actor and aper, instructing even performers on how to do their jobs. He seamlessly moves through personalities, depending on whom he is with. When the court has gathered to watch the players, Hamlet realizes he is being observed more than the performance, and so gives one of his own. Keep in mind the layers of punning with the word “nothing,” which in Elizabethan times was pronounced noting—he’s saying nothing as (1) a “never mind” evasion; (2) that her vagina lies between her legs; (3) that it’s empty because he’s not in it; (4) that it’s a fair thought that nothing is there, but that “fair” can be loaded with sarcasm and its own double meaning [he has already told her by this point get thee to a nunnery, which is a term also for a brothel, calling her a prude and a whore at the same time], so it’s fair and foul, has been corrupted but is also kind of nice, as he remembers it; (5) that the fair thought is also that everyone is noting them, that he’s been noted this whole play, and that he is noting and observing everything around him while he’s creating this performance.

Life is very complicated for Ophelia. She is certainly not dumb, but loving Hamlet is truly exhausting. And madness-inducing. And that’s before he accidentally kills her dad. Fun fact: as soon as he does more than think and speak, he begins to mis-note, thus killing the wrong person because it was his first impulsive act of the play. It’s the converse of Macbeth; as soon as he thinks and tries to plan, he makes a very bad decision and murders the king almost without realizing it. (Huh? IS this a dagger I see before me? Wait, what am I doing with it? Aaaah, it’s going into Duncan 27 times!)

Point being, Ophelia is hurt at his withdrawal. In Act II, scene i, when Ophelia returns the letters, at the urging of her father, she gives a speech so full of poetry it is clear there is a feeling beyond obedience to her father that moves her:

Ophelia: My lord, I have remembrances of yours,/that I have longed long to re-deliver;/I pray you, now receive them.

Hamlet: No, not I;/I never gave you aught.

Ophelia: My honour’d lord, you know right well you did;/And, with them, words of so sweet breath composed/as made the things more rich: their perfume lost,/take these again; for to the noble mind/rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind.” Translation: What has happened to you?

Let’s extend the intertextual analysis further. Macbeth sends Lady Macbeth a letter that is without any ambiguity. He is not a good internalizer. He has to talk everything through with his equal partner, his wife. He’s sort of like The Hulk or even Thor: a really great warrior but not destined to be the leader of men. His initial trajectory is the opposite of Hamlet’s but leads to a similar end—once you start doing stuff out of your nature, and which you know is wrong, you pretty much ruin the kingdom. To thy own self be true indeed.

Finally, Ophelia is being manipulated but she’s not dumb: Maybe if Hamlet sees his old letters he might get back into the mindset of when he wrote them. He might get back into bed with her. Because what she really needs is his loving tonight. And now we all need some chocolate.

“KEEP YOURSELF ALIVE”—Henry IV Part 1

Thomas Stothard [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Stothard [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

What You Need to Know: By Act V, Prince Hal is leading the battle against his parallel, Hotspur (Harry Percy). Falstaff is called up as well, and things are looking grim.

*

Queen’s opening number from their self-titled debut is Sir John Falstaff’s anthem: “But if I crossed a million rivers/And I rode a million miles/Then I’d still be where I started/Bread and butter for a smile…Now they say your folks are telling you/Be a super star/But I tell you just be satisfied/Stay right where you are/Keep yourself alive yeah/Keep yourself alive/Ooh, it’ll take you all your time and money/Honey you’ll survive…”

As he faces battle and Hal tells him he owes God a life, Falstaff replies: “’Tis not due yet; I would be loath to pay him before his day. What need I be so forward with him that calls not on me? Well, ’tis no matter; honour pricks me on. Yea, but now if honour prick me off when I come on? how then? Can honour set to a leg? no: or an arm? no: or take away the grief of a wound? no. Honour hath no skill in surgery, then? No. What is honour? A word. What is that word honour? air. A trim reckoning!—Who is hath it? he that died o’ Wednesday. Doth he feel it? no. Doth he hear it? no. ’Tis insensible, then? yea, to the dead. But will it not live with the living? no. Why? detraction will not suffer it. Therefore I’ll none of it: honour is a mere scutcheon: —and so ends my catechism.” He is ever the pragmatist, and we love him for it. But his tale of survival doesn’t stop there.

Hal sees him, after the battle, lying on the field, and offers this eulogy: What, old acquaintance! Could not all this flesh/Keep a little life? Poor Jack, farewell!/I could have better spared a better man: O, I should have a heavy miss of thee…

Falstaff then wakes from the dead, or gets up, and delivers the perfect coda to his previous speech, including one of history’s most famous lines, even if you didn’t know it came from Falstaff: if thou embowel me to-day, I’ll give you leave to powder me and eat me too to-morrow. ’Sblood, ’twas time to counterfeit, or that hot termagant Scot had paid me scot and lot too. Counterfeit? I lie, I am no counterfeit: to die, is to be a counterfeit; for he is but the counterfeit of a man who hath not the life of a man: but to counterfeit dying, when a man thereby liveth, is to be no counterfeit, but the true and perfect image of life indeed. The better part of valour is discretion; in the which better part I have saved my life.

Falstaff is the ultimate deflector and the king of brilliant rationalization. You get the impression he could have been a schoolmate of Hamlet’s, and matched him too, but he’s got too much of the Tao of Pooh in him, preferring the simple comforts of a hot capon and a honey pot. Nothing gets him down when there’s a practical solution, and he is able to deflect Hal’s many pranks—all but a final rejection. He’s the friend who always finds a way to get you to pay for him, but you always consider it a trade in your favor to be in such company.

On a side note, forget Orson Welles and other imposters; the one, true Falstaff is Roger Allam, and I absolutely urge you to get immediately the Globe production of Henry IV 1 & 2.

“THE HERO” & “FLASH’S THEME”: Let’s just call the whole album the Soundtrack for Henry V.(Only three of the songs actually have lyrics anyway. )

By Unknown engraver [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Unknown engraver [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

What You Need to Know: Henry V (formerly Prince Hal, son of Henry IV), has battled and defeated France. And now he’s marrying the princess of France.

*

In “The Hero,” Freddie sings: “So you feel that you ain’t nobody/Always needed to be somebody/Put your feet on the ground/Put your hand on your heart/Lift your head to the stars/And the world’s for your taking/(All you gotta do is save the world)/So you feel it’s the end of the story/Find it all pretty satisfactory/Well I tell you my friend/This might seem like the end/But the continuation/Is yours for the making/Yes you’re a hero (oooh yeah).”

This is the “marriage and babies for all!” finale, as is the post battle meet up between England and France, when King Henry offers marriage to Katherine of France and peace to everyone, after a long speech from the Chorus at the prologue of Act V:

“…Behold, the English beach/pales in the flood with men, with wife, and boys,/whose shouts and claps out-voice the deep-mouth’d sea,/which, like a mighty whiffler ‘fore the king,/seems to prepare his way: so let him land;/and solemnly see him set on to London./So swift a pace hath thought, that even now/you may imagine him upon Blackheath;/where that his lords desire him to have borne his bruised helmet and his bended sword/before him through the city: he forbids it,/being free from vainness and self-glorious pride;/giving full trophy, signal, and ostent,/quite from himself to God. But now behold,/in the quick forge and working-house of thought,/how London doth pour out her citizens!/the mayor, and all his brethen, in best sort,/like to the senators of the’antique Rome,/with the plebians swarming at their heels,—/ Go forth, and fetch their conquering Caesar in…”

“Flash -, Ah, ah,- King of the impossible/He’s for ev’ry one of us/Stand for ev’ry one of us/He’ll save with a mighty hand/Ev’ry man ev’ry woman ev’ry child/With a mighty Flash.” Oh, he saved them. With his mighty hand.

*

I hope you’ve enjoyed Part 2; more of your favorites are coming soon. Thanks for reading!